The Top 5 Deadliest Pandemics in History

| Pandemic | Cause | Duration | # of Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Black Death | Bacteria (yersinia pestis) |

1347 to 1351 | 75 - 200 million |

| 2 | Smallpox | Virus (variola) |

1520 to 1980 | 56 million |

| 3 | The Spanish Flu | Virus (H1N1 type) |

1918 to 1919 | 50 million |

| 4 | HIV/AIDS | Virus (HIV virus) |

1981 to present | 35 million |

| 5 | The Plague of Justinian | Bacteria (yersinia pestis) |

541 AD to 750 AD | 25 - 30 million |

Special Report

Special Report

What you'll learn:

Part One: The Plague That Changed The Course of Human History

Someone in Your Family Tree Escaped the Black Death

If you're reading this, that means someone down through your family line managed to survive one of the deadliest pandemics in all of human history and that was no small feat, particularly if they lived in Europe between 1347 and 1353. Not everyone managed that.

In fact, whole lines of families were wiped out. Generations gone. For you to be here, somehow one of your ancestors was immune to, recovered from, or otherwise managed to avoid catching one of the most infectious and deadly diseases humankind has ever known. Lucky for you those distant relatives, those survivors, went on to produce heirs that would go on eventually to produce, well, you.

The Black Death: The Plague to End All Plagues

The name says it all, but the exact source and why it was named "The Black Death" is not really well known and is probably forever lost in time. It was possibly named that way in the 17th century for the swollen lymph nodes that sprouted from the neck, groin and armpits of its unfortunate victims, which then swelled, bursting with thick, dark, clotted, "black" blood and pus. Or perhaps it was named for the bleak and "black" outlook on life is created through the death, sickness and despair it brought with it.

There were other names for it as well, "The Bubonic Plague", "La Pest", "The Great Mortality", but whatever it was named, it seemingly appeared out of nowhere, and raged through Europe, Asia and then moved on to some parts of Africa. It killed - and this is astonishing - upwards of 200,000,000 people worldwide over a short period of time. That's two hundred million lives lost.

It's difficult to overstate the devastation that the Black Plague wrought. Between 25 million and 50 million people died in Europe from the plague in the span of four to seven years from 1347 to 1353 alone (sources vary on the numbers and time-span). That would be like if all the people living right now in Romania or Spain died in a relatively short span of time, which is totally inconceivable thinking about it now in modern terms.

Imagine if 60% of the people living in Europe died within the span of a few months or years? It boggles the mind really, and although there are other theories floating around, the most widely accepted theory is that it all started with a tiny, microscopic, deadly little thing called Yersinia pestis.

The Bacterium that Changed the World

Yersinia pestis is a microscopic bacterium that is commonly accepted to be transmitted from fleas to rats and then from rats to humans. It is thought that the people in the middle ages often lived among rats and other rodents on a daily basis and thus many populated cities and other populated areas, especially in the countryside where there are a lot of rats, such as farms, became the perfect breeding ground for infection.

Recent research is suggesting that the spread of the plague was too fast for it to be propagated solely by rats, but let's face it, the middle ages are not exactly known for their cleanliness and sanitary conditions in public streets...or...perhaps they were... it seems we may have stereotyped the middle ages.

In any case, in the "bubonic" form of the disease, the theory is that the bacterium would infect the flea, the flea would infect the rat and the rat/flea would infect human beings through biting. The "pneumonic" form of the plague would become airborne through droplets, similar to today's Coronavirus pandemic. Some scientists now believe that the black death must have spread so efficiently through the airborne form of the plague rather than through rats alone (A.). Other scientists say it was Human body lice or fleas living on our ancestor's skin that did the job. (B.) Exactly how it spread so fast, and in what form, is the subject of much scientific debate today and is still somewhat of a mystery.

We do know that the specific form of the plague bacteria, or "bacillus", is an extremely stable and particularly virulent microbe so it spreads very, very easily. Whatever the case, how it started and spread, is a story unto itself and although no one really knows where it originated with certainty, maybe in the area near the Caspian Sea or the steppes of Mongolia, suffice to say it landed on the shores of Europe through large and complex networks of trade and commerce routes that were in place at that time.

Most of that trade during that time in history was done by ship. In fact, the world then was more globalized in terms of shipping and trade than the average person today realizes, and it was this human to human contact that allowed the tiny bacterium to spread so fast, up to 2 kilometres per day, and go on to devour so many lives in so many places. The middle ages, and ancient times in general, were far more sophisticated than we think. Especially in terms of trade and the networks that allowed that commerce, and subsequently disease, to flow.

The Terrible Human Toll

Nobody at that time, during the middle ages, was even remotely prepared for the devastation that hit them. In fact, one could argue that our modern-day pandemic preparedness would lack the effectiveness to combat such a disease as swift and terrible as the black death was. Even with our advanced modern medicine. It is not hard to imagine from where we stand today, battling our own global pandemic, that medieval society in the 14th century simply had no real understanding of the nature of the extremely contagious and complex disease that was spreading among them like wildfire.

They could not, therefore, organize any kind of efficient or effective countermeasures against it. The most they could do at first was to accept that maybe this was "the will of God" and maybe that they, in fact, deserved the suffering that was being brought down upon them from on high. This led to a type of religious fatalism that would lead to a lot of people on their knees praying, and who could blame them?

Meanwhile the plague raged on. The disease spread through families, homes, villages, towns, cities and through the countryside with terrifying speed and mortality that is staggering. It cut down, with its terrible scythe of bacterial death, men, women, children, adolescents, babies, cats (but interestingly not dogs), cows, chickens and pretty much everything else that moved around on land at that time.

While it is certainly true that medieval societies had to deal with a host of deadly and debilitating diseases during that time, the most common of those being: dysentery, malaria, diphtheria, flu, typhoid, smallpox and, everyone's favourite medieval disease: leprosy, it was also true that no disease killed on the scale of the Black Death. Its symptoms, and the speed at which they presented, was nothing short of terrifying.

The Symptoms

First, you would get fever and chills, or perhaps a headache. Then bulbous, black boils the size of an egg or a large onion would break out under your arms or on your groin or neck. These lumps could sprout anywhere there is a lymph node in your body. You would then become extremely feverish and weak and bedridden in your home, or simply fall where you were and lie delirious, murmuring nonsense in the street. Then the dark "buboes", or lumps would start to weep blood and pus. After that you vomited blood, your tongue swelled and you leaked diarrhea uncontrollably.

In some cases your extremities, your toes and fingers, would blacken and curl up, as they filled with gangrene. Very soon, in a matter of hours or days, you would be dead. So would the people who treated you and cared for you, perhaps a loved one or relative because they too would soon be infected. And the process would start all over again until your home or perhaps your whole village was empty of all the living souls who had inhabited it just a week or two before. The bacteria had finished its murderous job and the "Great Mortality" had claimed all its victims and moved on for more.

"A Single Death is a Tragedy; a Million Deaths is a Statistic."

It is difficult to imagine how life must have been for the people living through that period. A loved one could wake up with a fever in the morning and be dead less than 48 hours later, possibly even by the next day. Typically though, it took two to three days to die after symptoms first broke out. The quote, "A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic", is particularly true when viewing deaths through the long lens of history.

It sometimes seems that these distant events are so far away in time and happened in two far-away lands to relate to the acute pain and suffering that these people, these human beings, went through.

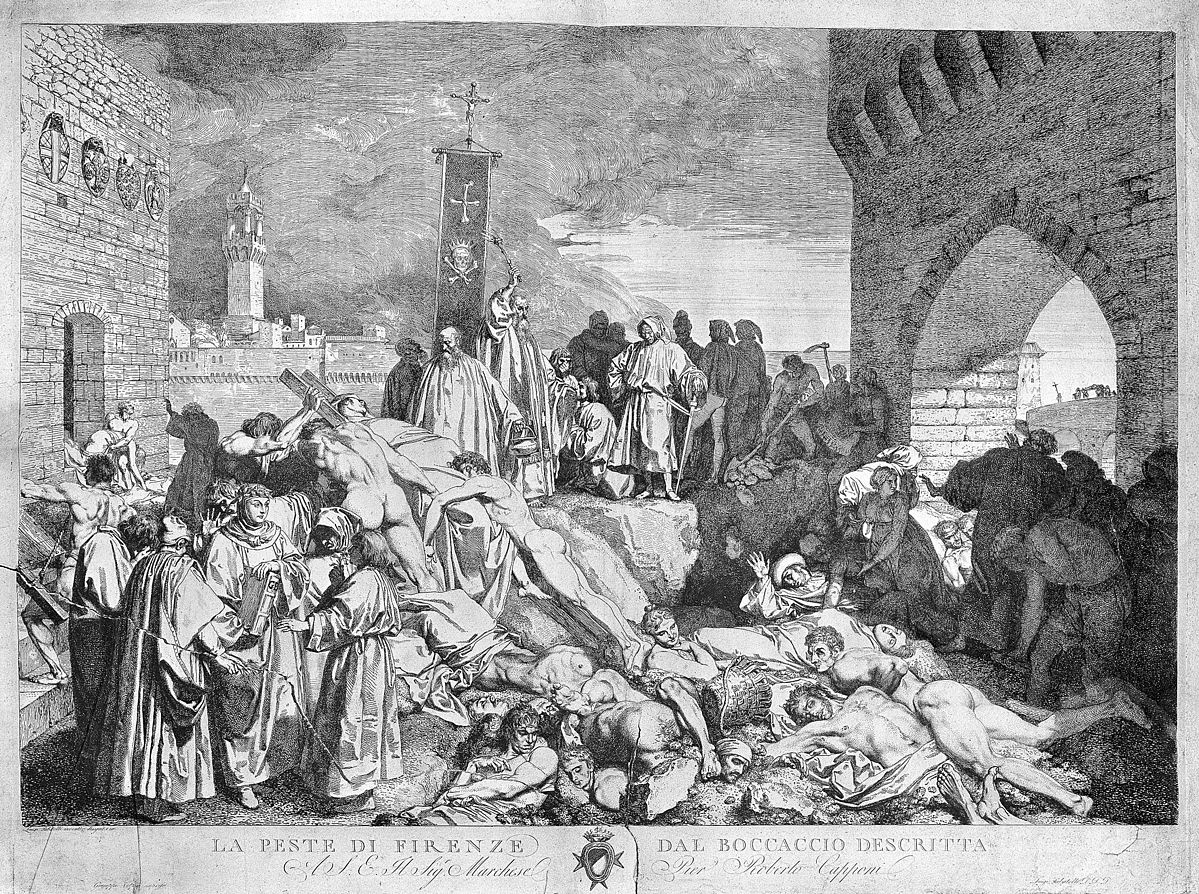

Plague victims are always portrayed in the medieval paintings from around that time as somewhat crude and stiff, and almost always in awkward poses that are hard to relate to today. While it is true that these paintings are not very relatable, we do tend to forget that paintings were the photographs of their time.

These artists, the ones that lived through the plague, were capturing the suffering and deaths of mothers and fathers and sons and daughters, uncles, aunts, grandmothers and grandfathers, little children, and toddlers.

They were, in essence, capturing the demise and shock of people that loved and were loved as much as we love our own families. It must have been a terrible, horrific thing to watch a person you love to die so horribly. The Black Death indiscriminately wiped out whole families. In countless instances, a father or mother would bury their children with their own hands. A written case that we know from that time was Agnolo di Tura, an Italian shoemaker from Siena who chronicled the events of the pandemic and who lived through the effects of the plague. Here are the events in his own words:

"The mortality began in Siena in May (1348). It was a cruel and horrible thing, and I do not know where to begin to tell the cruelty and the pitiless ways. It seemed to almost everyone that one became stupefied by seeing the pain...Indeed who did not see such horribleness can be called blessed. And the victims died almost immediately. They would swell beneath their armpits and in their groins, and fall over dead while talking. Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another...And none could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship. Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could, without a priest, without divine offices (last rites). Nor did the death bell sound. And in many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead." And I, Agnolo di Tura, called the Fat, buried my five children with my own hands. And there were also those who were so sparsely covered with earth that dogs dragged them forth and devoured many bodies throughout the city. There was no one who wept for any death, for all awaited death. And so many died that all believed that it was the end of the world.

Who can imagine the pain of a father who had to bury five of his children with his own hands? Did he possess a sheet to wrap his child, his little boy in before he placed him in the grave? Or was his young son buried in a common grave like millions of other unfortunates? Agnolo's is just one story from one man out of the millions that must have found themselves in similar, horrid circumstances.

Even though we now view these events through the long lens of history, this man's suffering is one that surely almost any person can understand or sympathize with. In just a few short days, months, or years, this disease ripped away from the sons and daughters of a generation of people and at the same time made orphans of the many children who survived which is another, often untold, story. The tone of writers, historians and artists from that time was somewhat apocalyptic, and one can easily see why.

The Logistics of Death

Just dealing with the massive amount of dead bodies on a daily basis was an enormous undertaking and they were literally piling up.

Dead bodies left lying around streets and houses obviously complicated matters even more than they already were, and the complete collapse of a reasonably organized society is a complicated thing to deal with.

One issue was horribly obvious though, the more decomposing bodies that you have stacked in the streets, the more disease you're going to generate for your city, town or village.

If you think that The Black Death was the only disease that medieval people were dealing with at the time you'd be wrong. As mentioned above, there was more than one serious disease floating around that the population had to contend with at the time. The scale of the problem at hand and all the potential problems that went along with it were simply enormous. The solution to this huge problem of what to do with all the suddenly appearing corpses was the same solution some countries are implementing during the current Coronvirus Pandemic sweeping it's way through our world right now. They dug mass graves.

When anywhere from 20% to 60% or even 80% of your population are at times, literally dropping in the street, you have a serious problem on your hands and you are forced to start with the disposal of human corpses and almost always in summer as the Bubonic Plague was not active during winter months as the rat fleas that spread the Black Death was not active during the winter season.

Mass graves are normally for poor people. In fact during the Bubonic Plague, like today, the pandemic affected poor people on a larger scale than it did the well off. The mortality rate among the poor during the plague was 5% to 6% higher than the mortality rate among the rich in those times. (C.) However, it is safe to say that due to the speed of the pandemic, not every wealthy person was afforded a proper burial either. Once again, another chronicler, Marchionne Di Coppo Stefani, gives us the perspective of what it was like for a city like Florence Italy to try and manage their pandemic dead:

"All the citizens did little else except to carry dead bodies to be buried [...] At every church they dug deep pits down to the water-table, and thus those who were poor who died during the night were bundled up quickly and thrown into the pit. In the morning when a large number of bodies were found in the pit, they took some earth and shovelled it down on top of them; and later others were placed on top of them and then another layer of earth, just as one makes lasagne with layers of pasta and cheese." (D.)

As Ole Benedictow, a plague historian, points out in his book "What Disease was Plague?", other than losing a loved one to this terrible plague, there was nothing worse for a human being and a religious person during that time in history, than to be forced to literally dump a loved one in a pit on unconsecrated ground without the usual benefit of last rites. (D.)

Christians believed at that time, that last rights and being buried in a proper church graveyard during a proper funeral, were essential elements to enter eternal heaven. Without those religious rites, their loved ones were at best, damned to eternal hell, or at the very least confined to limbo. The plague not only ripped children from their parents and vice versa, it also ripped through the very social fabric and traditions that European society was founded upon.

No disease that we know of has done so much to alter the course of human history. Yersinia pestis may be a tiny microscopic thing, but its impact on the human story was colossal, and it is something that is felt even today. In fact, if you are walking around London or Paris today, there are still bodies of people who died of the Black Death literally under your feet.

So How Did it All End Anyway?

It didn't. It is still with us today . The Bubonic Plague was around and killing people on a large scale before the events in Europe in 1346 (see the plague of Justinian above) and it flared up occasionally around Europe afterwards, such as in London in 1665 where it killed an estimated 100,000 Londoners in about a year and a half. The 14th-century epidemic is thought to have been brought under control sometime after 1353 by something that we can all identify with today: quarantine.

Historians believe that people simply stopped going outside and thus the infection rate is thought to have subsided little by little. Another factor that possibly contributed to the end of the epidemic of the plague at that time could be the fact that people started to practice better hygiene and that medieval people probably weren't as dirty as we think.

Other researchers think our bodies adapted to it and developed a resistance to the bacterial infection. Still, others think that this particular form of the Black Death killed itself out by killing everyone around it which is why pathogens such as viruses, often mutate to less lethal forms in a bid not to kill off it's hosts.

Although much of this is a historical mystery lost to time, researchers do know that the 14th-century form of the Bubonic Plague is not the same genetic form of the bubonic plague we have today.

One thing is certain though, although the Black Death did subside to manageable levels over time, and did come back every ten years or so to haunt the populations of Europe and the world, it never reached the heights of mortality that it did in the 14th century.

So the plague is still among us. In fact, bubonic plague has been reported in the United States and around the world in very recent times, and despite what many people may think, it never really went away. The United States alone reports between 1–17 cases of plague per year. It occurs in people of all ages from infants and toddlers up to people aged 96 years old. Most cases, over 50%, occur in people ages 12 to 45. The plague doesn't discriminate, it occurs in both men and women, though historically is slightly more common among men, probably because of increased outdoor activities that put them at a higher risk.

Plague in the US occurs mostly in the Southwest regions of the country. Specifically: Northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, Colorado, California, southern Oregon, and far western Nevada. Thankfully the modern-day bubonic plague, which makes up 80 to 85% of all plague cases, is highly treatable with antibiotics. (G)

Modern Science Comes to the Rescue

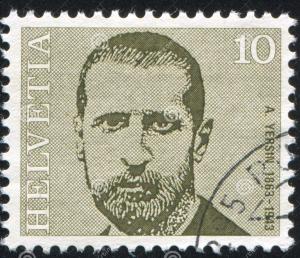

In 1894, Alexandre Yersin, a French/Swiss biologist and Kitasato Shibasaburo a bacteriologist from Japan, almost simultaneously discovered the source of all this, the little havoc-causing bacterium yersinia pestis, the reason for so much misery and upheaval over the centuries. Interestingly, scientists are still fighting over who should get the full or partial credit for that discovery, because let's face it, scientists are more pugnacious and cat-fighty than we think, especially when it comes to getting credit for things (please read T. Butler's extremely interesting account of these events here).

Yersin, who was obviously on the case, began to treat plague victims with a horse serum in 1897 and noticed a drop in the death rate of 51%. Of the people who were treated with the serum, only 13% died from the plague whereas 64% of the people who did not receive the horse serum died. There was apparently some serious side effects as a result of injecting horse serum into humans, such as serum sickness and anaphylactic shock, but hey, that's how science works (E.).

While studying dead bodies in Hong Kong where a recent outbreak had taken place, he noticed a lot of dead rats in the streets which naturally piqued his curiosity. He collected the deceased critters and brought them back to his lab. While examining the lymph glands of some of the dead rats, he found the same bacillus that he had found in human tissues and voila, he was the first to make the historically important, but somewhat causal connection between rat mortality and human epidemics.

Yersin didn't make the flea-rat connection at that instant, but the beginning of the end of a centuries-old mystery was starting to come to light and for the most part due to his work. Later, it was Jean-Paul Simond, a French scientist that discovered the transmission of plague-carrying bacteria from rodents by flea bites in 1898.

Suffice to say a lot of smart people are involved in these discoveries along the way, and it is often a chain of previous events that lead to a big discovery or improvements on smaller ones. Even though scientists get a little scrappy when it comes to credit for discoveries, at the end of the day science is really a team sport.

At first our Black-Death-causing bacteria was named Bacterium pestis but then went through other name changes until it was named Yersinia pestis in 1970 in honour of its discoverer. So it's pretty clear who won that particular fight as the name of the bacteria isn't "Shibasaburoia" pestis.

Should We be Worried?

Probably. In 2011 the DNA of Yersinia pestis was found in human graves from the Justinian and medieval plague eras and scientists studying it found that the DNA was remarkably similar to the modern-day plaque-causing bacteria (F). It's not hard to imagine that this could happen again. A few short months ago who would have thought that our world would have been plunged into such chaos so quickly? Today's Coronavirus pandemic, still raging its way across the globe, has given us a rare insight into what kind of havoc a bacteria or virus can wreak upon a human population. SARS Covid-19 brought and is still quite capable of bringing, modern-day healthcare systems to their knees and all in a relatively short span of time. It has gives us a modern taste of what medieval people must have experienced during the Black Death outbreak of 1347.

The truth is scientists who dedicate their lives to researching infectious diseases and people in the know like Bill Gates, have been warning us about our readiness to handle a global pandemic like this for years now. We need to listen. While it's true that while the bubonic plague is still around, the possibilities of the "Black Death" coming back in the way it did in the middle ages is slim to none thanks to antibiotics. But what about antibiotic resistance? In 1996 in Madagascar, two multidrug-resistant strains of Y. pestis were found and one of those strains was completely resistant to all the antibiotics the scientists threw at it. As the CDC mildly puts it, this is "worrisome".

In the end we as human beings are masters of our own fate. If we don't put the time, energy and resources into curing, eliminating or preventing infectious diseases and especially preventing antibiotic resistance our path to doom is clear. We must secure our future and the future of our children. If we don't then we are bound to suffer the errors of our past and make no mistake, Yersinia Pestis is waiting.

Noel James Riggs,

Owner and Head Writer, Top 5 of Anything.com.

Contact me at njrtop5ofanything@gmail.com

Top 5 Special Reports sources:

A. Katharine R. Dean, Fabienne Krauer, Lars Walløe, Christian Lingjærde, Barbara Bramanti, Nils Chr. Stenseth, Boris V. Schmid: “Human ectoparasites and the spread of plague in Europe during the Second Pandemic"

B. Guarino, Ben. (2018). “The classic explanation for the Black Death plague is wrong, scientists say"

C. Benedictow, Ole J. (2005). History Today: "The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever"

D. Benedictow, Ole J. (2011). "What Disease was Plague?: On the Controversy over the Microbiological Identity of Plague Epidemics of the Past".

E. Hodgkins, Ryan, Ditchburn, Jae. (2019). Yersinia pestis, a problem of the past and a re-emerging threat.

F. Butler, T. (2014). Plague history: Yersin’s discovery of the causative bacterium in 1894 enabled, in the subsequent century, scientific progress in understanding the disease and the development of treatments and vaccines.

G. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Maps and Statistics: Plague in the United States.

Sources:

Top5ofanything.com Global Pandemic Research 2022.

List Notes:

List data is the top 5 deadliest pandemics in human history as of July, 2020. All figures are best estimates. This top 5 list may include official, semi-official or estimated data gathered by www.top5ofanything.com.

*A chronicler is a person who writes descriptions of historical events as they happen.